The Apprenticeship Years

I have always had an extreme respect for the craft of theatre. Over the years, decades, this has only deepened. Now I refer to the “Mystery” of theatre, a term that stems from medieval Guild terminology. From the beginning I knew I knew nothing. No-one in our family or in our family’s acquaintance had any relationship with the Arts, let alone the theatre, I never had the luxury of any formal theatre training when I started. In retrospect I realise I was somewhat envious of the students at the National Theatre School that were part of our circle at the McGill Players’ club. As President, I offered an entire class of seven students graduating on the technical side the opportunity to direct a lunchtime show when I was running the Club. In return i was snuck into various classes at the school by my colleagues. Essentially, like most of my generation, I learned by doing.

“Old Synagogue Is Getting In On The Act”, reads the headline of the back page of the weekly East London Advertiser. Three ragged hippies with hammers converting a synagogue into a theatre. What you can’t see behind us in the picture is the pile of scrap lead we had, the previous night, ripped off of the roof of a Victorian warehouse that was being demolished in the neighbouring alley. If you look at the balustrade framing the balcony over our heads, you can just make out the inscriptions, some in Hebrew, some in English, in gold paint, the names of the individuals who had donated to the founding of the synagogue in the early Thirties. We were able to preserve them by covering them over with newsprint, which we then painted black.

The reporters, as I said, knew what they were doing. Once the story was published, they phoned our landlords, the Jewish Orthodox Federation of Synagogues, to get a reaction and were told that there was no way that a play could be performed in a synagogue. The boys had their real story. A week later the sandwich boards proclaimed the front page story in the East London Examiner: “Jews Ban German Play in Synagogue.”

The story was picked up by some main line press in their national editions across Great Britain, with our two young reporters scoring their byline in the Times and Guardian. Thanks to their generosity, our landlords, the Rabbis running the Federation of Synagogues, never acted on the threat to ban us, and we went ahead and ran the play, and a theatre is born.

Jungle opened on January 27th, 1972 immediately putting the Half Moon on the London theatre map. As the reviews below attest, the critics generously approved. Running in the West End at the same time was a revival of Threepenny Opera staring Vanessa Redgrave… which the critics panned, some even saying if you want to see a real Brecht play, go to the Half Moon.

In The Jungle Of The Cities

January, 1972

The founding of The Half Moon was driven by my desire to direct Bertolt Brecht’s early play, In The Jungle Of The Cities. An amazing cast of experienced British actors who agreed to work for a cut of the box-office in the hopes that they would “be seen” by casting agents and working directors. Will Knightly, father of Kiera Knightly, was a member of the cast. We opened on January 27th, 1972. Play was a critical hit and immediately put the Half Moon on the London theatrical radar screen as you can see from the reviews. Will Knightly, as did other cast members, went on to a respected career in British Theatre. Maurice Colbourne, my Half Moon co-founding partner, was an actor of unique gritty presence. He was soon snapped up by the BBC and film producers to play working-class leads in major series. Leaving me to run the theatre.

A production photo. Set was a white boxing ring floor with a jungle of scaffolding nicked from local buildings sites. Back wall of the set, covering the “Ark” in which the Torah would have been kept in the former synagogue, was a wall of corrugated iron (also nicked from local building sites). The wall was meticulously and laboriously painted in horizontal stripes of clashing chromatic colours in a Bridget Riley op-art style. When lit with different colours the wall shimmered like the air coming of the pavement of the scorching mean streets of Chicago, where the play was ostensibly set. We never had the lighting equipment to fully exploit the concept.

That is Will Knightly, dead centre. I am always chuffed when I see his bio in various places and he proudly mentions being a founding actor member of the Half Moon Theatre.

The Squatting Movement

With the success of Jungle, it was clear that I was going to be spending most of my life in the East End around the theatre. We started to look around for a place to live to save on time and transportation costs.

Ann Petit who was one of our squatting neighbours and a leader in the movement wrote a detailed article in xxx about our lived campaign to secure affordable housing for ourselves and the 100 of thousands other homeless in London at the time.

(LINK) Her memoires are much more comprehensive than mine would ever be. One small error with her article on ? page after we had been evicted she talks about “smashing the Locks” to regain access to the homes we had been evicted from. the locks were not “smashed” but “gemmied” , that is pried open with a crow bar. I know, because I was the guy with the gemmie (crowbar) and took the initiative to pry the locks off the doors.

Will Wat? If Not, What Will?

May 1972

After the success of Jungle, the Half Moon was a going concern.

But Brecht had only attracted an audience of actors and seasoned theatre-goers from other parts of London. I was set on a theatre that spoke to and for its own community. For my second production I looked for something with a more local connection. When I discovered that the 1381 People’s Rebellion ended with a final confrontation between Richard II and a throng of 50,000 rebels on Mile End Common, just a short distance from the location of the Half Moon, I started researching the history. Spent a month in the British Museum. (Tried to sit in Karl Marx’s seat as often as I could, if it was free.) Found all the songs and the final speech of Richard II’s in dusty tombs. Even wrote a couple of first drafts of the scenes. Playwright Steve Gooch agreed to come on as the writer and did a tremendous job creating a story line and assembling the material and helping devise a period feel for the language and accents. I also assembled a 200 lb anvil from a local blacksmith and a couple of out-of-tune church bells from the local Whitechapel Foundry (Where the first American Liberty Bell was cast!!) and built a 98 gallon hogshead drum, using a recycled Salvation Army drum skin stretched over a wine barrel from the docks, to beat time for the rebel march on London. When struck, the drum was so large it set the whole Half Moon building vibrating. (See the poem: The Drum) The power of the production came to a large extent from the intimacy of the space, the proximity of the audience to the rebelling “peasants.”Take a look at some of the reviews. John Mortimer in the Sunday Observer even wrote, “one of the best in my term as a critic”. Irving Wardle in the Times wrote: ‘The impact of the performance is honest, direct and theatrically electrifying…”

We were packed out in the final weeks, and probably could have run the play for months, but unfortunately had already planned a production of an adaptation of a popular boys Brit comic adventure series, Dan Dare. The production turned out to be utterly inane, in fact worse. The aliens invading Britain in the story were seen as a veiled xenophobic depiction of the influx into England of Ugandan Asians, after Idi Amin drove them out of Uganda. The production almost succeeded in derailing the left-wing nascent Half Moon brand.

The Silver Tassie

October 1972

Summer of 1972 I managed a brief holiday in Canada, after being away for two years. The excuse for Judit and my trip home was to get married on the front lawn of her mother’s home in Côte-des-Neiges. We had been together for over three years, but only one month after getting married and returning to London, we went our separate ways. (See the poem Food For Thought.) Maurice had decided to direct Sean O’Casey’s play Silver Tassie. Great play about the irrational carnage of WWI. As head carpenter, I set about building a transverse stage through the space. Worked nicely. Also ended up playing a small part, my first time trying an Irish accent. Canadian rural dialect helps. A decent production but Maurice was not really a director, more an animator of energies, a patient builder of self-confidence in his cast. Sometimes his directorial comments were too deferentially oblique. Michael Irving played the lead with an unfocussed energy, an undefined character. Too bad, Michael had all the talent needed to be a great actor.

Ripper!

January 1973

Continuing my dream of trying to bring the local community into the theatre, I commissioned a play about Jack The Ripper. Trying to solve the mystery of the identity of the Ripper is a national obsession in Britain. A play about him would be sure to rouse interest. Some of his murders actually were committed a stone’s throw from the Half Moon itself. I was less interested in the person/identity issue, than in the political background that created the social conditions where the murder of innocent women was a mirror of what was happening in society as a whole. 19th Century British Capitalism was, as far as I was concerned, the guilty party. The play was a bit thrown together, had a rough-hewn music-hall energy. Bill Dudley, who went on to become one of the most celebrated and award-winning British theatre designers, did the set. 1988 was both the year of Jack the Ripper’s rampage in the East End, but also the period when a large influx of Jewish immigrants, driven from Russia by the Pogroms, were arriving to find new homes. The local businessmen from the “Shmata” trade were clamouring to exploit the immigrants as cheap labour for the garment industry. My favourite moment in the play was an early morning job market scene. We had just witnessed yet another night-time murder and butchering of a female sex worker. As the (anonymous) murderer slinks away, the lights slowly come up on a foggy adjacent square, with businessmen searching for experienced tailors to exploit in their factories shouting: “I need a hand, a good hand.” “Need a good pair of eyes, eyes.” “Who has some strong arms and a good head for me?” Capitalism butchering the workers metaphorically.

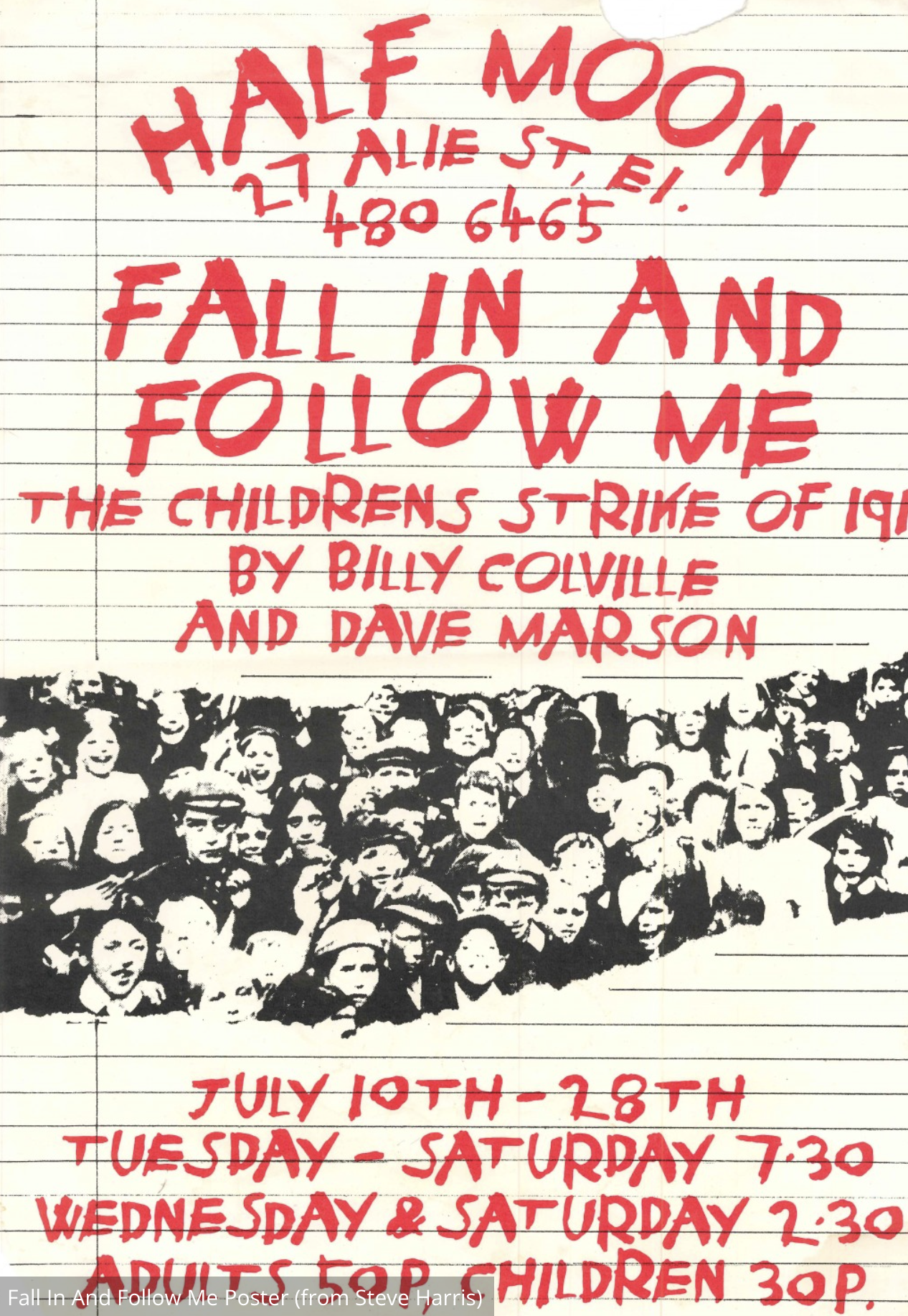

Fall In And Follow Me

July 1973

Living near the original location of the Half Moon was Raf Sammuels, a professor of working class history at Ruskin College, Oxford. He had begun to frequent our plays and supported the community objectives of the theatre. He introduced me to one of his students, Dave Marson, a docker from Hull, Yorkshire. As part of his Ruskin studies, Dave had been researching a children’s school strike that had swept the British Isles in 1911. I brought East End actor and burgeoning playwright, Billy Colville, into the mix and the result was, with Dave’ research and Billy’s playwriting, a superbly moving play about the local events in Stepney, East London during the 1911 school strike.The children were striking over the use of corporal punishment in their schools, and wanted monitors to be paid, and wanted time off to be able to work outside of school and support their families. The School strike was very much inspired by the example of the striking dockers of the time, and schools were closed all across Great Britain by the flying pickets of the striking students. We set our play in and around the local Ben Jonson Primary School and included a cast of six local boys. Our professional actors played the adults, the parents, policemen and teachers. A group of 6 eleven and twelve year-old local boys, none of whom had ever acted before, played the striking students. It was also my second collaboration with set designer Bill Dudley who after the Half Moon, went on win a few Olivier awards for his design genius working for the National Theatre and the RSC. Michael Mackenzie, now a celebrated Montreal playwright and director, got his first job in the theatre as stage manager on the show. He remembers with awe, Bill Dudley working through the night spending hours hand-chunneling out the individual bricks in his set. The result was a stunning verisimilitude to a real brick wall. (See the photos)

On the eve of the opening of the play a school board official turned up at the theatre and tried to close the show down. We did not have the statutory separate dressing rooms, nor a designated child minder for the kids. We were illegal. I called a meeting of the all the boys’ parents. To a Mom and a Dad they all said, “Fuck the School Board authorities. My kid is goin’ on tha stage tonight.” The play went on. It was a hit.

Towards the end of the run, one of the boys got seriously ill. In tears he proclaimed he could not do the show. We held a crisis meeting, ten minutes to go before “curtain.” The five boys sorted it out amongst themselves. “I’ll take ‘is lines in this scene, you take ‘em in the second scene…”, etc. The show went on, the audience non-the-wiser. See the detailed and highly intelligent article on the play and the strike itself in the Times Literary Supplement written by Chris Searle.

The spirit of Trotsky is alive and well in the body of an 12 year-old Stepney boy as he rallies his fellow students to go on strike in 1911.

The boys read with pride about their striking achievements in the local paper.

Cover of the Ruskin College published version of the play.

Get Off My Back

Oct-Nov 1973 and toured Tower Hamlets December 1974

Text goes here…

Henry IV

March, 1974

Directing my first Shakespeare. I conflated parts one and two of Henry IV into a reasonably acceptable piece (running-time-wise) of theatre. You overlap the battles from each part and conflate some of the characters. Not a new idea in the history of the plays. My God, what hubris. Trying to pull off the impossible with no resources. Maurice Colborne was an amazing Falstaff. That much I remember. He had a humanity that was seductive and spoke the language with prosaic clarity that had none of the Royal Shakespeare Company’s effete, artificial acting style. We gave him a purpose built plastic sack of water as a false belly under his costume. You could hear the water sloshing inside him as he strutted around the stage. It meant he could actually be taking a huge loud piss while addressing the audience for his, “honour” monologue. I had this strong sense that all of the characters in the play were “acting” out something, duty, or friendship, loyalty, courage… but that inside/underneath there was a different reality going on in the character. So I had this ingenious, but impossible to realize, concept that each of the main characters would have an alter-ego puppet next to them for the entire performance. The puppet was responsible for acting out the subtext of what a character was really thinking while the character was acting in a manner that was publicly appropriate. Falstaff puppet, for instance, could be picking his nose or scratching his balls while Falstaff character was addressing the King, or the Prince. A few actors who came to see the show, puzzled about the concept, when it was explained to them, they just said in that understated British way, “Guy, why did you not just trust your actors to handle the subtext?” Yes, it was an impossibly complex attempt to render something simple that was cute, but unworkable, at least in the time we had to rehearse it. Will Knightly was playing a number of characters including the Bard’s humourous, if not racist, swipe at Scotland, the Scotish Lord Douglas. “As heart can think there’s no such word spoke of in Scotland as this term fear.” (Spoken with a cod Scotish brogue.) During the last week of the run Will was offered a nice paying movie contract and had to be let go. So I stepped in and played his parts for a week. Oh, boy. Designer Bill Dudley, who had turned the Half Moon ingeniously into a Cheapside Tavern as the set for our production, and who would go on to win numerous Olivier Awards for his work with the RSC and the National, was in the audience one night to see me step in for Will. He said afterwards he had never laughed so hard in his life, and had nearly fallen out of the balcony.

3P-0ff Opera

July 1974

· by Billy Colvill

A Brecht-style musical unabashedly ripping off The Threepenny Opera plot. An East End factory owner closes his works and has it burned down in order to cash in on the development boom. At this point his workers tried to occupy the factory.

Poster designs by Martin J Walker and printing by Walker and Brittain, Red Dragon Print collective.

Spare Us a Copper

September 1974

TEXT GOES HERE

LINK TO EACH VIDEO

Driving Us Up the Wall

February 1975

Encouraged by a trio of young community workers, we embraced the idea of a youth theatre workshop associated with the Half Moon. The trio had been working with a group of kids from the near by Isle of Dogs council estate, developing a play, a kind of docu-drama based on an actual court case the boys had been implicated in. The kids had been arrested for climbing over the dock wall near their homes and joy riding brand-new cars lined up and ready for transport around the wharf. The judge trying the kids had been seriously outraged as, “Those jaguars were bound for export!” , as if the kids single handedly were going to ruin the British economy. Rehearsals hit a rough spot with most of the kids trying to opt out. When the project looked like it was going to go belly up, the community workers begged me to step in. I drove the theatre van down to the estate and rounded up the kids, literally grabbing the more recalcitrant members of the group by the scruff of the neck and tossing them in the back of the van. The kind of action that would probably have me arrested today. But it worked. We drove back to the Half Moon, picked up the rehearsals and were able to get the show on. In the end, as can be seen from the show program we got a few of our regular actors, like Alan Ford and Terry Docherty (Dougherty) to volunteer to play the adults for the show and we even seconded fellow Canadian, Peter Hartwell, future award-winning Royal Court designer, as production manager. (He went on to a celebrated design career in Canada after he too returned home, designing at Shaw and Stratford and Avro Arrow for me at the NAC and Canadian Stage.) Peter Sunderland in his Half Moon interview, gives a sense of the chaos around the initiative. In the end the play ran for a week and attracted a local audience who cheered the kids on. It was the first production of what would become the Half Moon Youth Theatre which survives and thrives to this day.

Paddy

March-April 1975

TEXT GOES HERE

Half Moon Alie St.

The Alie Street Synagogue converted into the half Moon Theatre. Lovely painting that shows the facade from the mid-Seventies. Built in the Thirties, a time when anti-Semitism was rife in the East End, the actual synagogue part was recessed into the back yard and the frontage made to look like a normal dwelling. Presumably this was a mild form of camouflage.

My commitment to testing theatre for one year had stretched to nearly five years abroad. Judit and I had been home briefly in the summer of ’72 to get married in Montreal. (Once married, ironically, we split up within a month.) Life was too exciting, encounters all encompassing, politics all-engrossing. Running the theatre had been 24/7for me. We each found different partners. I became enthralled with and partnered up with Pam Brighton, after I hired her to direct Brecht’s play St Joan of the Stockyards. By mid 1975 I had learned a great deal of my craft.

Half Moon Video Interview

In 2016 the Half Moon Theatre got a nice foundation grant to do a video legacy project that covered the founding and early days of the theatre. As the artist who spurred the 1971 transformation of an empty synagogue in the East End of London into a public performance venue we named the Half Moon, I was asked to do a long interview. The occasion brought back lots of questions. What on earth did we think we were doing? They were heady days. I was the crazy Canuck, from a country that was still creating itself, I believed anything was possible. Between many cups of tea I was able to nudge the stodgy Brits into accepting that opening a new theatre was possible. We decided to do it and we did it. On less than a shoe string within one year we built one of the most exciting Fringe theatres in England. A theatre that today is one of the most respected and well-funded community/youth theatres in the UK.

Stages of the Half Moon, The Half Moon Heritage Project:

Guy Sprung

Co-founder, First Artistic Director, 1972 – 1975

Guy co-founded Half Moon Theatre in 1972 with Maurice Colbourne and Michael Irving and was the first Artistic Director. He directed the opening production of In the Jungle of the Cities. Other productions he directed included Will Wat, If Not, What Will?, Fall In and Follow Me, Get Off My Back, Ripper!, The 3p Off Opera and Paddy. He also directed the community productions Spare Us a Copper and Driving Us Up the Wall.

Before joining Half Moon Theatre, Guy was Assistant Director at the Schiller Theater in Berlin. He returned to his native Canada in 1975, where he has been involved with many companies…

LINK TO Full transcript